Tuesday 9th August 2022

Opinion piece written by: Alex Stevenson

I have followed the commercial peat debate for 14 years now with it ebbing and flowing in profile through the media. Over that period, I have become more and more clear in my thoughts on the subject as more research and evidence is presented. Unfortunately, the two main arguments against using peat in commercial horticulture of habitat/biodiversity loss and GHG emissions are based on a fundamentally incorrect premise; that horticultural peat is harvested from pristine peat bogs.

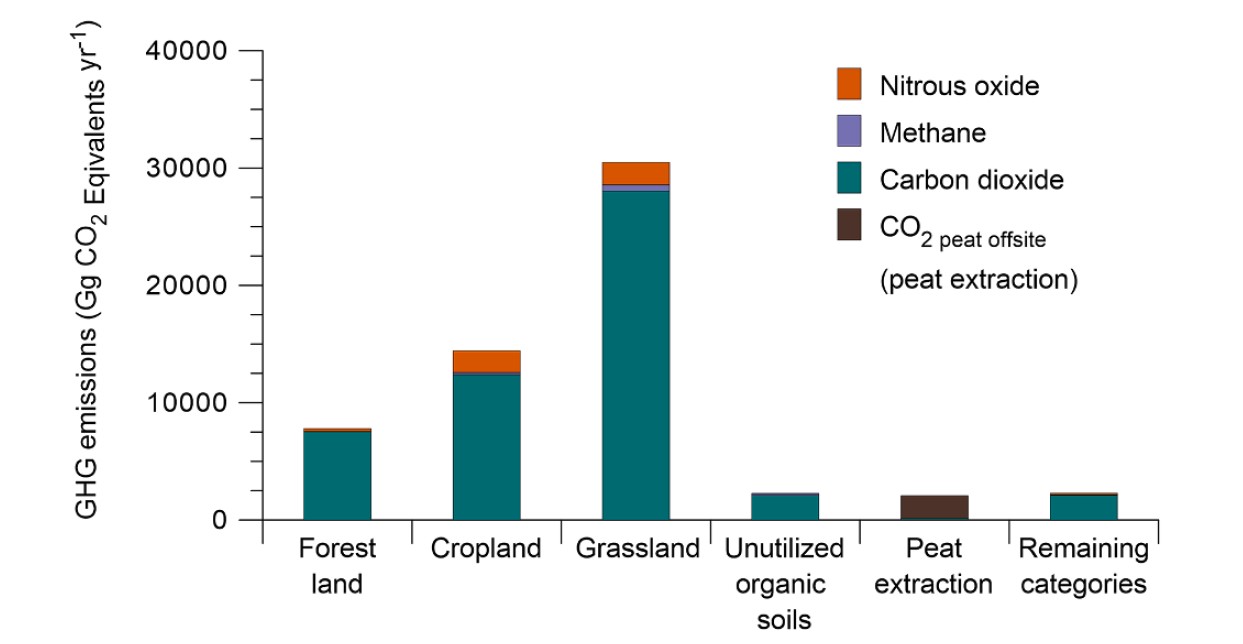

Pristine peat bogs are wonderful thing; they are biodiverse, act as long-term carbon stores over non-human timescales and provide other environmental benefits such as filtering and storing fresh water. Horticultural peat in the UK however, has never been harvested from pristine bogs. It is harvested from areas drained between 150 and 300 years ago by humans for agriculture and habitation. Research by B. Tiemeyer, et al demonstrates that the lowest CO₂ emitting activity that can be carried out on these degraded lowland bogs is peat extraction. Lower than forestry, agriculture, grazing, urban development and even than leaving the land completely unutilised. Rewetting long term degraded lowland bogs is not an immediate option as the ground profile needs to be dropped. Therefore, the lowest carbon releasing use of these already degraded bogs (surface milling) actually funds and returns them to a state where they will be a well-functioning bog once again.

GHG emissions from German peatlands by land-use category and GHG including peat extracted for horticulture based on the land-use in 2014 taken from; A new methodology for organic soils in national greenhouse gas inventories: Data synthesis, derivation and application B. Tiemeyer, et al, 2020.

So the carbon emission arguments against peat are more emotive than scientific, but undeniably peat does have a GHG impact, but it is significantly lower than previously presented evidence suggests and with almost no biodiversity loss. Beyond GHG’s peat ticks all the other sustainability criteria; it’s local, renewing (the UK & Ireland lay down far more sphagnums annually than will be used in horticulture), light to transport (30-50% of a substrate’s CO₂), supports high quality local jobs (10,000 in Southern Ireland alone), will improve biodiversity over time, performs excellently, requires less use of mineral fertilisers than PF alternatives, requires less use of fresh water than PF alternatives. The use of 50-60% peat in a substrate means you can quickly, easily and economically replace the remainder with the only truly renewable low GHG option; wood. This is by using woodfibres, bark and composted bark fines. All the other options that are available at anywhere near the scale required can only be used in small percentages (5>30%) and still require a well performing dilutant such as peat.

The argument that you can’t have peat in horticulture and restore UK and Irish peatlands needs to be decoupled, because it is quite clear that the most sustainable thing to do is both! Have a local well governed small scale peat industry while continuing to restore upland degraded bogs wherever possible. If we are going to meet our net zero targets, we are going to get there through pragmatism not reactionism.

Summary of commercial alternatives available at scale (>200,000m³ annually):

Coir: Although in some instances use up to 100% is possible, we are just exporting our issues abroad. The industry creates immediate rather than historic habitat loss, uses and pollutes huge volumes of fresh water abroad and in the UK. It is energy intensive to transport, compress and decompress, pH is too high and has a large Nitrogen drawdown.

Composted Greenwaste: If carried out where the input material is controlled to eliminate contamination with herbicides, heavy metals and human pathogens, which is not happening in the UK but is successfully being carried out in Germany, it can be used up to 20%.

AD Waste: Extremely high EC and nutrient levels mean it can only be used up to 10%. DEFRA now state 65,000ha, 1% of all the UK’s arable land is used to grow maize as feedstock for AD plants. A massive hidden footprint and completely unsustainable. Contamination with microplastics and herbicides is also common.

Loam/Clay: Excellent buffering properties however it is replacing one emitter with another. Because of the heavy processing required and high weight for transport only use up to 10% is realistic.

Woodfibre/Bark/Composted Bark: The only true circular alternative over human timescales. Large Nitrogen consumption in use, low water holding capacity, potential for hydrophobic hyphae and heavy weight of composted bark are significant drawbacks. Competition for materials from the energy and building industries is huge driving up prices. If the volume of materials were available locally it is possible to use in combinations up to 80%.